|

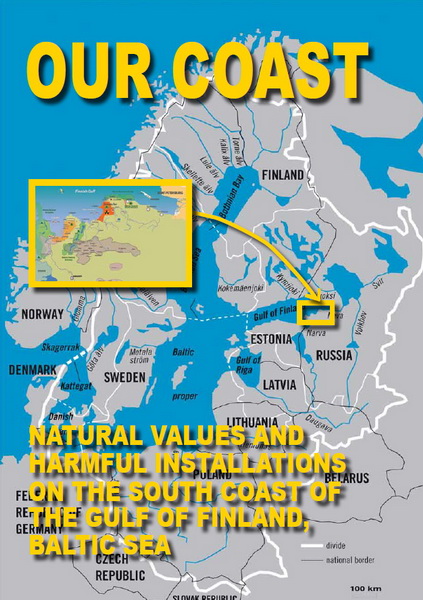

The South Coast of the Gulf of Finland |

|---|---|

| Natural Values and Harmful Installations |

|

Concept of a decommission plan for old nuclear power reactors |

|---|---|

| Guiding Principles from Environmental NGOs |

Russian nuclear power officials visit Vermont for ideas, expertise in decommissioning process

Randolph T. Holhut Commonsnews

A combination of past nuclear accidents and the accumulation of wastes from more than six decades of nuclear activities at the site have made the area surrounding Mayak one of the most contaminated in the world, with significant concentrations of strontium, cesium and plutonium found within a 100-kilometer — or 60-mile — radius of the facility.

Oleg Bodrov, chair of NGO Green World, was part of a Russian and Norwegian delegation that toured Vermont last week. He spoke at Brooks Memorial Library in Brattleboro on SaturdayBodrov said that there are about 500,000 cancer victims living in that zone, and the childhood cancer rate around Mayak is 14.1 per 100,000, as of 2007-08, substantially higher than in other parts of Russia.

Oleg Bodrov, chair of NGO Green World, was part of a Russian and Norwegian delegation that toured Vermont last week. He spoke at Brooks Memorial Library in Brattleboro on SaturdayBodrov said that there are about 500,000 cancer victims living in that zone, and the childhood cancer rate around Mayak is 14.1 per 100,000, as of 2007-08, substantially higher than in other parts of Russia.

In addition to handling its own wastes, Russia is taking in radioactive material from Britain, France and Germany, which is turning into a profit center for the Russian government.

Natalia Mironova is a former engineer who is the head of the Movement for Nuclear Safety, an environmental group in Russia formed by a group of women concerned about radioactive waste. She said that Russia is positioning itself to be “the superpower of energy.”

Russia already substantial natural gas reserves and an equally substantial uranium mining industry, she said. Reprocessing the world’s nuclear fuel fits into that strategy.

Aging plants, no easy fixes

Of the 13 Russian reactors that got authorization from Rosatom, the Russian Federal Nuclear Agency, to extend their operation, Bodrov said 11 are of the same design as the Chernobyl reactor. An accident at these reactors, many of which are located in more populated areas, would have even worse environmental consequences than the Mayak or Chernobyl disasters.

Russia and the United States, as the first nuclear nations, have the oldest nuclear reactors that require decommissioning and clean-up. This raises significant environmental and safety issues in both nations.

What’s the solution? Bodrov said setting up a well-funded decommissioning process is the first step, with the management infrastructure to do the job.

In Russia, he said stronger laws and regulations are needed to protect the public and regional councils — similar to the regional planning commissions in Vermont — should be formed to serve an advisory role and represent the public in any deliberations.

Finally, he wants to see host cities of nuclear facilities get sufficient funding to make the transition to economically and ecologically sustainable development.

Bodrov acknowledged that the United Stares is much further along in this process than Russia, but there is one common factor between the two nations. “One region gets the ‘clean’ power and another region gets the waste,” he said.

Among the other delegates that made the trip to Vermont were Olga Tsepilova, deputy chairman of the Green Russia political party; Andrey Ivanov, head of the Murmansk Regional Parliament Committee on Environment and Agriculture; Sergy Pavlov, a legislator and leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia; Julia Korshunova, an coordinator for the decommissioning project of NGO GAIA in the Russia city of Appatity; and Pavel Tishakov, an advisor for the Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority.

The tour was sponsored by the New England Coalition.